It is hard to identify where the suffering first enters a family — especially because suffering so easily compounds, finding new expressions in each generation, until somebody finally says: stop.

I never met my grandfather, Harry Havemeyer Webb, who died of complications from alcoholism in 1975, a few years before I was born. I know from my mom that he was a sweet and kind-hearted man, but didn’t have the tools to heal himself from his addiction to alcohol, which came into his life in his thirties, many years after his tenure as a service pilot in World War II had concluded.

By the late 1950s, his marriage to my grandmother, Kate de Forest Jennings, was failing — plagued by infidelity, a lack of intimacy, and a worsening disassociation from one another exacerbated by mutual drinking.

-

My grandparents and their kids, late 1950s — with my mother in the middle

By the time my grandmother decided to leave him for a swordfishing captain (named George Seemann), his daughters were away at school, and he found himself living alone in the house at High Acres Farm, grappling with isolation and loneliness, and turning more and more to booze as a means of escape.

-

My grandfather’s collection of miniature liquors

According to Sammy’s letter, Harry would put on his old Air Force uniform at three o’clock in the morning, make himself a cocktail, and walk around the house, alone.

In this ritual, I recreate Harry’s experience, serving as his proxy. I borrow his old Air Force uniform from the collection of the Shelburne Museum, which was founded by his mother, Electra Havemeyer Webb.

-

My grandfather’s Air Force uniform from World War II

I take his place in his bed — the same place where my mother spent her final moments, resting on his monogrammed “HHW” pillow.

-

My grandfather’s pillow case

I sit up suddenly, screaming, and stumble across the hallway into his dressing room, where I step into his old uniform, which fits me more or less perfectly. I go into his old bathroom, look in his mirror, put on his tie, and clip it into place. I fasten his monogrammed belt buckle to tighten his pants.

I go downstairs, moving through the empty house, finding my way to the bar closet that continued to display his collection of alcohol, even forty years after his death.

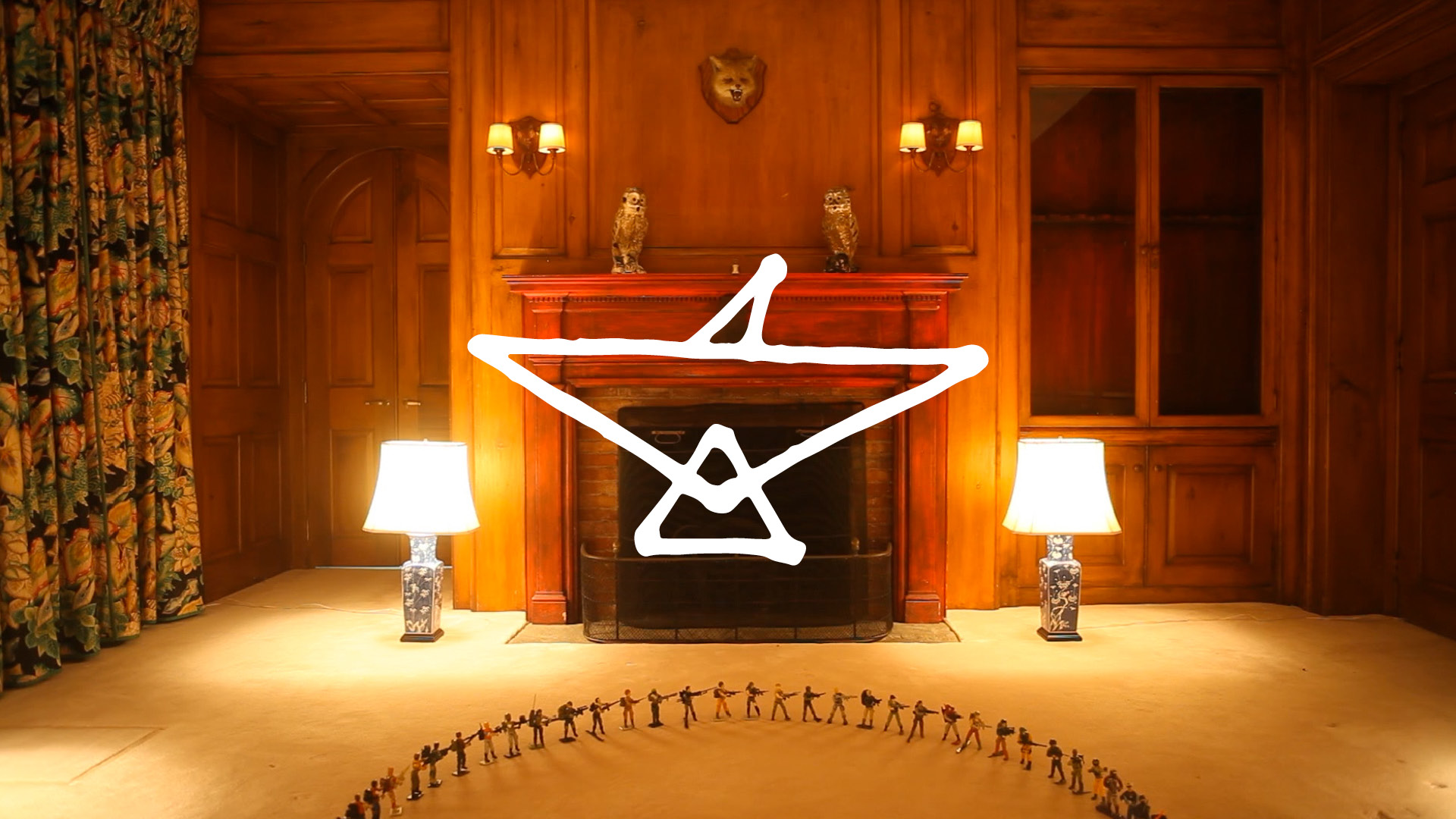

I take a swig from his bottle of “Old Grand-Dad“ whiskey and step into the room where Process of Elimination was performed — still decorated with the matching heads of bucks he shot and killed while hunting in the Adirondacks.

I sit down between his hunting trophies, and thumb through a stack of his photographic memories — parents, childhood, sports, lovers, wedding, war, children, divorce, solitude — making his memories my own.

These memories are intercut with flashes of scenes from the house — fox head trophies, owl statues, a wasp walking across his silver monogrammed lighter, my childhood collection of G.I. Joe figures, their plastic weapons.

Then the flashes shift to the outside lawn, where his old red parachute is spread across the dying grass, littered with alcohol bottles and “action figures” tumbling through the ground, as I writhe around in this historical detritus.

-

My grandfather’s parachute

I gather up the parachute and proceed to the old red “Trophy Room” building at the edge of the woods, which is hung with animal heads killed by Harry and his parents during family hunting trips to Alaska in the 1930s and 40s.

The room is lit by the same twin sets of halogen work lights from Use a Hammer and Hall of Mirrors — illuminating a brown bear, a moose, a caribou, two rams, several deer, a bobcat, a porcupine, and an owl. The animals watch as I arrange the alcohol bottles in orderly lines on the floor.

I stand one of my childhood G.I. Joe figures at attention in front of each bottle — linking my experience of war with his.

-

My grandfather’s collection of miniature liquors

-

My childhood collection of G.I. Joe figures

I make a concoction of all 100 alcohols in an empty whiskey bottle.

I take a swig of this potent elixir.

I pour the liquor solution into his monogrammed silver bowl set atop a butane camping stove, which I ignite with his monogrammed lighter.

I use red parachute cord to hang the empty bottle upside down above the boiling solution, to catch the rising vapor.

I wait patiently as the evaporated spirits enter the bottle.

-

Collecting the spirits — with the birch canoe from See Glass hanging from the ceiling

Once the liquid has been fully evaporated, I take down the bottle with the captured spirits, and I walk outside to meet the dawn.

I place the bottle on a wooden altar, set at the edge of the High Acres Farm field. I pick up Harry’s hunting rifle, put a bullet in the chamber, walk back twenty paces, cock the gun, and take aim.

With a single shot, the bullet shatters the bottle — “freeing the spirits” into the landscape, where they can be subsumed and finally healed.

I return to the High Acres Farm house to find a small plate of Chrysanthemum flowers (also known as “Mums”) waiting for me on the slate patio.

I take them to the edge of the field and toss them to the spirits of the land.

The G.I. Joe figures have now exchanged their plastic guns for flowers — passing tiny floral bouquets from soldier to soldier.

The morning I completed this ritual, demolition began on the old Main House at High Acres Farm, Harry’s home for many years.

Over the next eight months, the house was completely transformed through a total “gut renovation” — producing the warm and welcoming space it is today.